I constantly make notes on paper - always ideas and sketches, never "journal entries" as such - many of which are never revisited in any meaningful sense. Often, a sketchbook will have bits of ideas scattered amongst actual working drawings, they will have unfinished notes at the back or halfway through turn upside-down to begin afresh: no matter, I can nearly always remember the thought-processes I was exploring. As my colleagues, friends, workmates and followers-from-afar know, I am a fairly intermittent blogger but the relationship between my blogging and my workflow is marked: I will often blog things - or at least post photographs of works-in-progress to Flickr. My reasons for this are twofold: one, I want a record of how I achieved a particular end and; two, I want to share that process with others.

Didion suggests "I always had trouble distinguishing between what happened and what merely might have happened, but I remain unconvinced that the distinction, for my purposes, matters". For my purposes, this is exactly what matters. She continues, "[...] I sometimes delude myself about why I keep a notebook, imagine that some thrifty virtue derives from preserving everything observed" which I can agree with, but she is right: there is a quality of self-delusion about the whole process. This is made very apparent when I consider that I have uploaded images of my sketchbooks to Flickr and that I have blogged them. To precisely what end? The works-in-progress are more comprehensible, even if merely analysed in the strictly economic sense of "marketing", but why upload images of the sketchbooks, especially as I am very clear about their purpose to me? More perplexingly, why do I get so many comments from people thanking me for sharing them?

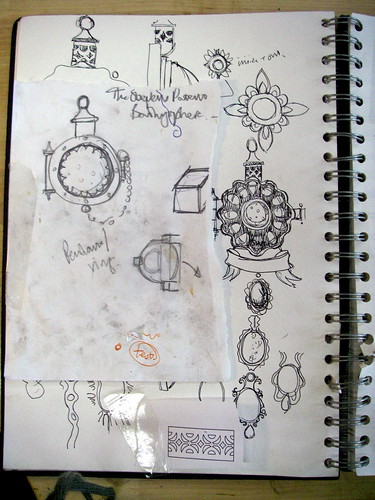

Page from one of my notebooks.

Part of my Calvinist discomfort comes from the implicit understanding that "[...] our notebooks give us away, for however dutifully we record what we see around us, the common denominator of all we see is always, transparently, shamelessly, the implacable 'I.'" I have to confess to finding it difficult to being as open as this, to sharing even the relatively impersonal details of my sketchbooks and my works-in-progress. I am meticulous in managing my public persona, right down to setting individual privacy settings on my photographs on Flickr. Does this mean that I am being dishonest? Doesn't this undermine the whole purpose of blogging and sketchbooks?

Didion suggests at the end of her essay "we are all on our own when it comes to keeping those lines open to ourselves: your notebook will never help me, nor mine you" and in a sense, she is right; but it seems to me that elements - selected fragments - of notebooks can be very helpful, especially in gaining an insight into the creative process or the thoughts behind any given work. She suggests that there are two types of notebook, "[...] the kind of notebook that is patently for public consumption, a structural conceit for binding together a series of graceful pensees" and "[...] something private, about bits of the mind’s string too short to use, an indiscriminate and erratic assemblage with meaning only for its marker".

I would argue that the "bits of mind's string too short to use" are, when edited carefully, the most interesting assemblages.

*Of course any actual analysis of Facebook by someone with a reading age high enough to understand Didion's comment would instantly lead them to the conclusion that they were, in fact, more interesting than most others!